Following the Way of the Cross tonight, Pope Benedict remarked to the crowd:

Following the Way of the Cross tonight, Pope Benedict remarked to the crowd:"Following Jesus on the way of His Passion," the Pope said, "we see not only His passion but that of everyone who suffers in the world. This is the profound intention of the prayers of the Via Crucis - to open our hearts and help us see with the heart."

The Fathers of the Church, said the Pope,"considered that the greatest sin of the pagan world was insensitivty and hardness of heart. That is why they loved the prophet Ezekiel, who said, 'I will take away your heart of stone and give you a heart of flesh.'"

To convert to Christ, he said, meant "to receive a heart of flesh, sensitive to the passion and suffering of others." "

Our God is not a remote God, who is untouchable in His beatitude. He has a heart of flesh, He took on flesh precisely to be able to suffer with us and be with us in our sufferings. He became man to give us a heart of flesh and reawaken in us the love for the suffering and the needy."

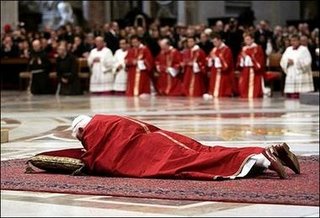

Earlier in the day at St. Peter's Basilica the Pope began ths service prostrate:

I could be wrong, but the carpet looks much like the one that Pope John Paul's coffin rested on at his funeral.

I could be wrong, but the carpet looks much like the one that Pope John Paul's coffin rested on at his funeral.

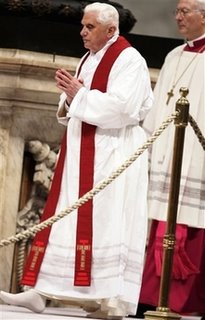

He held up the cross for veneration (a very good image with St. Helena in the background):

Then removed his shoes, to venerate the cross: